Current Regulations for Privacy and Consent

Privacy of personal information and consent to its use is regulated at the national level in most Western countries. These guidelines mostly focus on the Canadian context, but also look briefly at the US, EU, and UK. The European Union’s 2018 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is the most stringent set of privacy guidelines and laid the groundwork for regulations in other Western countries. Several levels of regulation inform the framework for ethics boards that institutions must implement to grant ethical clearance to research applications. Canada has the Privacy Act, Personal Information and Protection Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), and the Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS 2); in the US, regulations include the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA); and the UK has the UK GDPR. Beyond government regulation, privately and publicly held datasets may have terms of use and licensing agreements with additional layers of restrictions.

When preparing to work with medical (or any) datasets, artists need to be mindful of all the legal frameworks, to identify whether and what gaps exist in these frameworks, and, if the work is international, the differences in regional legislation. Legislation is geographically dependent, so if data is created in the UK but it is accessed in Canada, it is Canadian legislation that applies to the data.

In Canada, the Privacy Act (1985) protects “the privacy of individuals with respect to personal information about themselves held by a government institution and that provides individuals with a right of access to that information” (Government of Canada 2021). PIPEDA (2000) covers how businesses handle personal information. In 2020 the Government of Canada proposed the Digital Charter Implementation Act with the goal of increasing individual control of data and transparency regarding how companies use data, but the charter is yet to be passed.

The US Privacy Act (1974) “governs the collection, maintenance, use, and dissemination of information about individuals that is maintained in systems of records by federal agencies” (United States Department of Justice 2014). There are also other acts such as the Video Privacy and Protection Act (1988), which restricts audio visual usage; the Cable Communications Policy Act (1984); and HIPAA (1996), which protects sensitive patient health information. At present, there is no one act that regulates data privacy in the United States; rather, privacy data is governed state by state.

The European Union’s GDPR (2018) protects “natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data” and applies to companies and public bodies (European Parliament 2016).

In the UK, the Data Protection Act (2018) is a modified version of the EU’s GDPR: “The GDPR, the applied GDPR and this Act protect individuals with regard to the processing of personal data” (Data Protection Act, United Kingdom Legislation, 2018) and “controls how [an individual’s] personal information is used by organisations, businesses or the government”.

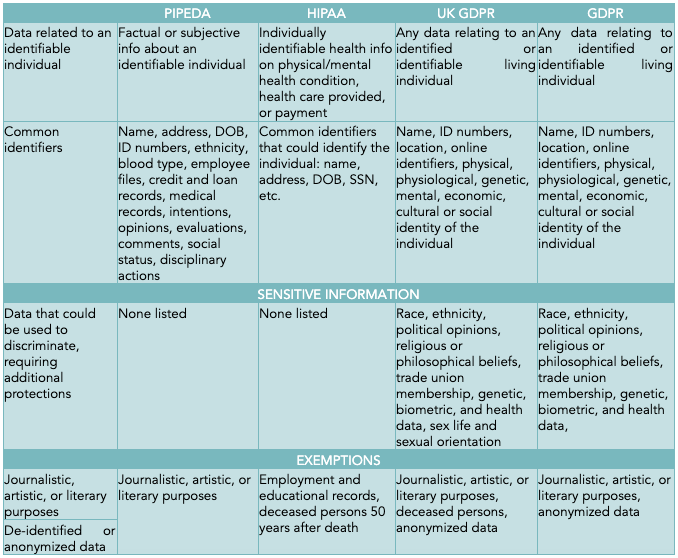

Personal Data

The definitions of personal data for each nation’s legislation are fairly exhaustive. Broadly, personal data is defined as data related to an identifiable individual and includes demographic information—common identifiers such as name, address, date of birth, and identification numbers. Within personal data there are categories of data that are considered sensitive and require additional protections, including race, ethnicity, political opinions, and religious affiliation. Sensitive data is considered in the following section.

Exemptions from privacy legislation include de-identified or anonymized data, or when personal data is used for journalistic, artistic, academic, or literary purposes. The exemption to journalistic, artistic, academic, and literary purposes is related to freedom of speech, while the exemption of anonymous data assumes that it would be difficult to identify an individual from anonymous data.

Differences between legislation is less easy to generalize. Not all jurisdictions extend protection of privacy to the dead, and what is considered personal data and what is considered sensitive data is not consistent. When working internationally, it is recommended that the local regulations for use of personal data be consulted.

Sensitive data

There are some important legal caveats to the collection and use of personal data that is considered more sensitive. UK and EU GDPRs both have separate categories for sensitive data that requires additional precautions. UK GDPR specifies data as sensitive when it is related to an individual’s race, ethnicity, political opinions, religious and philosophical beliefs, trade union membership, genetic, biometric, and health data, sex life, and sexual orientation; while GDPR’s sensitive data classification includes data related to race, ethnicity, political affiliation, trade union membership, genetics, biometrics used for identification, and health data.

In Canada, Chapter 9 of the TCPS 2 specifically addresses the use of data originating from First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences, and Humanities Research Council of Canada 2019c). Use of this data requires that additional criteria be met, including actions addressing community engagement, recognition of cultural protocols, and respect for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit sovereignty. Additionally, secondary use of personal data—use of data that was not specified at the time of collection—originating from these communities is not exempt from ethical review.

Table 1: Comparison of Privacy Regulations across Western Countries

Biometric Data

Biometric data is a category of sensitive data that includes biologically derived information (voice, fingerprints, iris scans, DNA, and genetic information) that is used to verify an individual’s identity. In Canada, this type of data is subject to the Privacy Act and PIPEDA. The Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada (2018) notes some of the unique privacy challenges that biometric data pose, including covert collection, cross-matching with other data to identify an individual, and secondary information extraction from the data that was not consented to at the time of collection. For example, an iris scan used for identification may also yield medical data and disclose health-related information about a person when the individual has only consented to use of the scan for identity verification.

To avoid unethical use of biometric data, the Canadian government suggests that biometric data be used “for verification rather than identification,” as a best practice for avoiding the inappropriate use of data. Other jurisdictions are creating special regulations to provide further protections. In the United States, Illinois, for example, enacted the Biometric Information Privacy Act in 2008, which outlines requirements for written notice of collection, obtaining written consent, and standards for how biometric data is to be handled (Illinois General Assembly 2010).

Exemptions

As explained earlier, journalistic and artistic/creative work is exempt from most data protection regulations. Another common exemption is the secondary use of anonymized or de-identified data. Returning to Dr. Nwabueze’s research on privacy law and images of the dead, the GDPR also exempts data from deceased persons (with no specification of time after death), while HIPAA specifies exemptions fifty years after death.

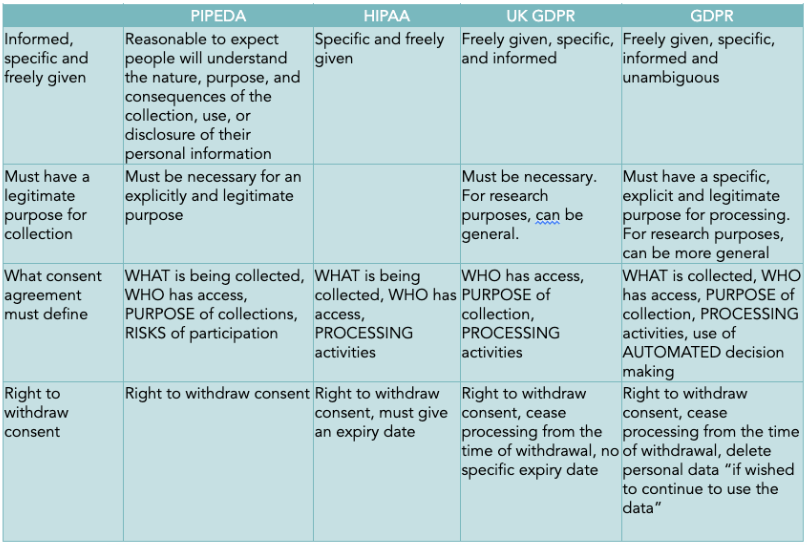

Consent

In order to use personal data, consent must be obtained from the individuals to whom the data relates. The GDPR and UK GDPR stipulate in Article 4.11 that consent must be “a clear affirmative action” that is freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous. Consent must be obtained separately for each purpose (Radley-Gardner, Beale, and Zimmermann 2016; Information Commissioner’s Office 2021). GDPR, HIPAA, and PIPEDA require consent forms to be written in plain language that is easy to understand (Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada 2018b; Radley-Gardner, Beale, and Zimmermann 2016), and all four policies require consent forms to include the purpose of collection and a process for withdrawing consent.

Requirements for consent are otherwise inconsistent. PIPEDA does not explicitly require either consent forms or for the entity collecting the data to be identified (Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada 2018a), and GDPR does not require disclosure of who will have access to the data. Only PIPEDA and HIPPA require what is being collected to be

Table 2: Comparison of Consent Regulations across Western Countries

specified (Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada 2018a; United States Department of Justice 2020), while both EU and UK GDPR include how the data will be used or processed and require separate consent for separate purposes (European Parliament 2016; Information Commissioner’s Office 2021). Only GDPR requires consent to be necessary, and while UK GDPR and HIPAA address whether consent can expire, HIPAA requires an expiry date (Alder 2021) and UK GDPR specifically indicates that an expiration is not required (Information Commissioner’s Office 2021). PIPEDA also includes several unique stipulations that have been recently introduced. PIPEDA requires the provision of information on the potential risks and harms of participation, the provision of different levels of detailed information at the data subject’s request, that the reasonable expectations of the data subject be met, and that consent be dynamic and ongoing, renewed when there are significant changes to the use of data. Additionally, Canada’s Digital Charter Implementation Act, proposed in 2020 and still in development in 2022, intends to modernize and simplify meaningful consent, develop a process by which individuals can withdraw their consent and request that their data be disposed of, require that businesses make their algorithms transparent, and strengthen the protection of anonymous data (Government of Canada 2020).

Issues of consent are further complicated if someone is deceased. In those cases, a personal representative for the estate or next of kin may be able to provide consent depending on the specifics of the request and situational context.

Additional Data Regulations in Academic Research

In Canada, use of personal data is further regulated by the Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS 2). Updated in 2018, the TCPS 2 stipulates that any research involving human or human biological material must undergo ethical review. The core principles around which the policy is structured are respect for persons, concern for welfare, and justice. However, research is exempt from ethics review when the data it uses is either “publicly available through a mechanism set out by legislation or regulation and that is protected by law or in the public domain and the individuals to whom the information refers have no reasonable expectation of privacy”. Data that falls into the first category of publicly available data includes data that is found on government websites such as demographic statistics or vital statistics, open-access datasets (e.g., OpenNeuro), or private datasets that are available through subscription. Data that falls into the second category of data in the public domain includes data found on public (i.e., open or not set to private) social media profiles or “found” data such as digital or physical images. Copyright, intellectual property rights, and dissemination restrictions may still apply to publicly available data, and private datasets available through subscriptions also come with terms of use that dictate further restrictions on how the data may be used.

Research is also exempt from ethics review if it involves the “secondary use of anonymous information, or anonymous human biological materials, so long as the process of data linkage or recording or dissemination of results does not generate identifiable information” (TCPS2 2018). Secondary use of data is when data is used for a purpose other than that which was specified at the time of collection; anonymous data is data that has had some of the data points removed so that the individual from which the data was derived cannot theoretically be identified. Most publicly accessible datasets would fall under this exemption, with particular attention paid to how the use of the data could compromise the anonymity of the data subjects. In the age of social media, smart devices, and the vast amount of data they produce, the standard for anonymization has come under scrutiny since the availability of personal data can now compromise anonymization methods. The threat lies in both the wide range of information that can be inferred through location-tracking data (Baron and Musolesi 2020) and the ease with which individuals in anonymous datasets can be re-identified by cross-referencing demographic information (Rocher, Hendrickx, and de Montjoye 2019). As the TCPS 2 notes, “Rapid technological advances facilitate identification of information and make it harder to achieve anonymity” (TCPS2 2018, 18). The TCPS 2 does not, however, provide any guidance on how to avoid or navigate potential ethical problems.