A Mirror with no reflection

Excerpt about A Mirror with no reflection from Know Thyself as a Virtual Reality essay by Lianne McTavish

Artist Nicholas Hertz uses virtual reality technologies to convey the work and experience of the body in a different place, notably the MR machine. This scanning device is “non-invasive” because it produces three-dimensional, detailed images of the soft tissues of the body without damaging them with surgical incisions or x-ray radiation. The MR imaging process relies on a strong magnetic field and radio waves to excite and detect the change in the movement of protons found in the water of living tissues. Those undergoing an MR scan can nevertheless find it traumatic. They must lie prone and unmoving inside a large magnet that produces strong vibrations and a repetitive mechanical sound. They might also be worried about what the resulting scan could reveal, as MR images are most often employed for diagnostic rather than artistic purposes. The machine is thus another liminal space, but unlike a recuperative bedroom, it exists in between knowing and not knowing about the dangers that might be hidden within the body.

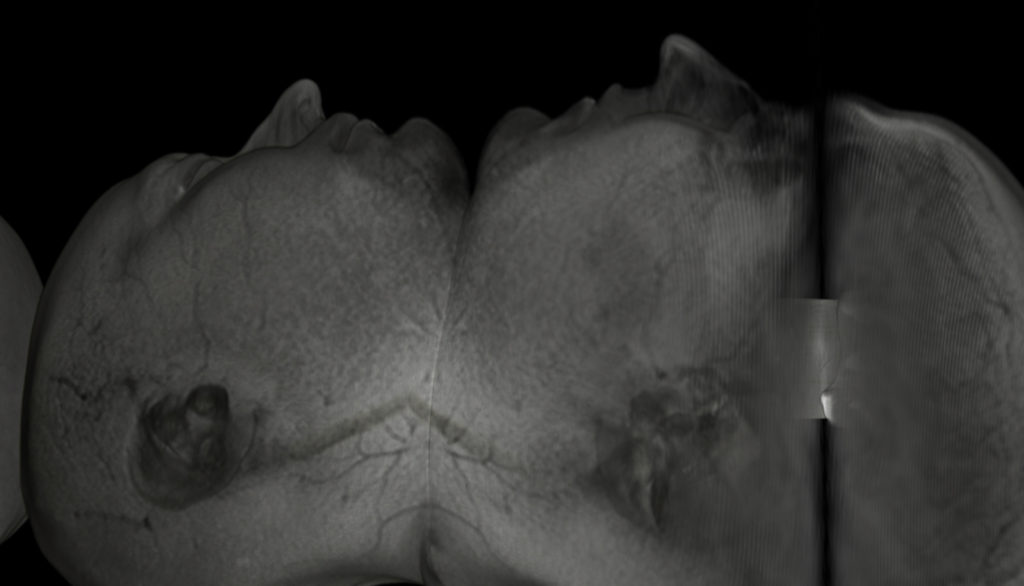

The first scene in Hertz’s VR artwork, A Mirror with No Reflection, conveys this anxiety. The visitor is subject to sequential MR scans of Hertz’s head, torso, and pelvis that automatically move toward them, becoming objects of fear or contemplation rather than renderings of the physical body. When the datasets finally stop within the VR artwork, they surround the visitor and place them within the three-foot-wide circumference of an MR bed. While visitors experience the claustrophobic effect of the MR machine, they are also subject to an exponential increase in the sound and vibration of the controls. Hertz created this soundscape with Melobytes, an artificial intelligence (AI) software. It translated images from the artist’s datasets into sounds that Hertz could manipulate. When the uneasy sounds combine with the alarming images, they ask those experiencing the VR artwork to consider the disconnect between their bodies and such technologies as the MR machine and the VR headset.

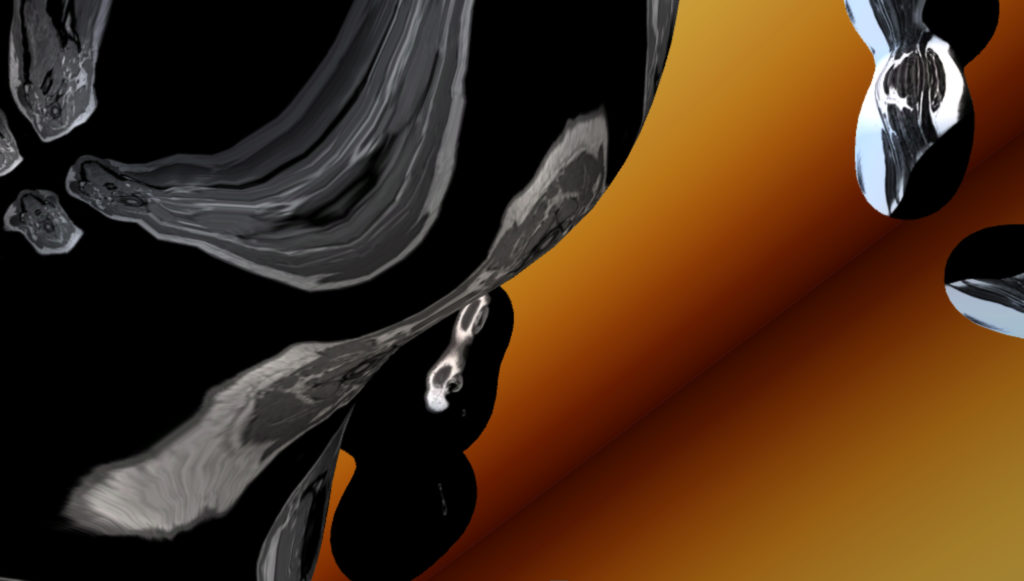

Hertz then provides the visitor with some respite and agency in the next virtual landscape. It potentially offers a warmer, more hopeful experience, with medical datasets transformed into fluid drops that organically shift within an orange scene reminiscent of a sunset. The visitor can move through this dreamlike setting but will continue to struggle to discern the details of the images. Their mirror-like surfaces are both attractive and illusive, with MR scans that distort and resolve. Though these scans may appear to offer reflections of the self, they remain unrecognizable; they provide a viewing experience that is alienating and uncanny, one in which self-knowledge remains obscure. The two scenes in Hertz’s artwork suggest that though we may look to medical imaging technologies with hopes of seeing ourselves more intimately, they remain estranged from us, casting doubt on what is real.

Nicholas Hertz (he/they) is a queer white-settler artist based in amiskwacîwâskahikan (Edmonton). Their work and research is an invitation to question the relationship between documentation and representation. Through their print, photo, and installation based work, the viewer is situated in parallel with their gaze as they recontextualize moments of their lived experience. In these dissected frames, spaces– like the backseat of an Uber, a motel room ceiling, and a Berlin flat– become anthropomorphized. Conversely, elements of the body within these spaces become objectified and foreign.

Artist – Nicholas Hertz

Unity development – Walter Ostrander

MRI Research Associate – Peter Seres