Marilène Oliver, Scott Smallwood, Liz Ingram and Bernd HildebranDt

Excerpt about Your Data Body from Know Thyself as a Virtual Reality essay by Lianne McTavish

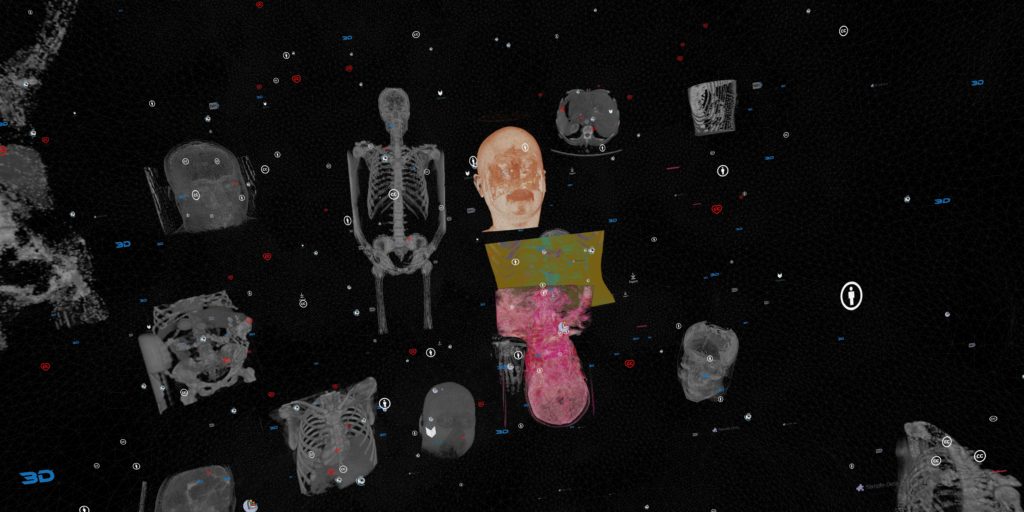

Whereas My Data Body seeks to make visible all the data that humans now generate and are responsible for as individuals, Your Data Body troubles how we interact with, and are responsible for, the data of others. Your Data Body is not constructed from Oliver’s personal data. Instead, it is comprised of open-access anonymized datasets and donated medical scan datasets. In this VR artwork, the visitor automatically moves through multiple levels, which change every three minutes. The first scene features content sourced from such open-access databases as the Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA), National Library of Medicine, Embodi3D, and Open Neuro. Originally acquired for scientific and medical research, the medical scans have been anonymized and made available for secondary research by means of creative commons licensing. Using the VR controllers, those experiencing Your Data Body can pull the scanned body parts from the web structure, and place them elsewhere in the scene; they can resize and recolour the anonymized body parts. These possessive acts are nevertheless countered by reminders of the regulations that limit the use of the datasets. If users bring a scanned body part toward their ear, they will hear an automated voice reciting the information that was posted alongside it in the open-access database. They can also examine the logos and icons that emanate from each body part to reveal their institutional or commercial identities and related usage agreements. In most cases it remains unclear, however, whether or not the person whose body was scanned has consented to the digital dissemination of their medical data. The sounds include a choral work sung by the music department’s Madrigal Singers, chanting “anon, anon, anon” to envelop the scene and enhance this uncertainty. These sounds are part of the overall soundscape co-composed by Scott Smallwood and graduate students Catherine Bevan, Mari Alice Conrad, and Thomas Powell.

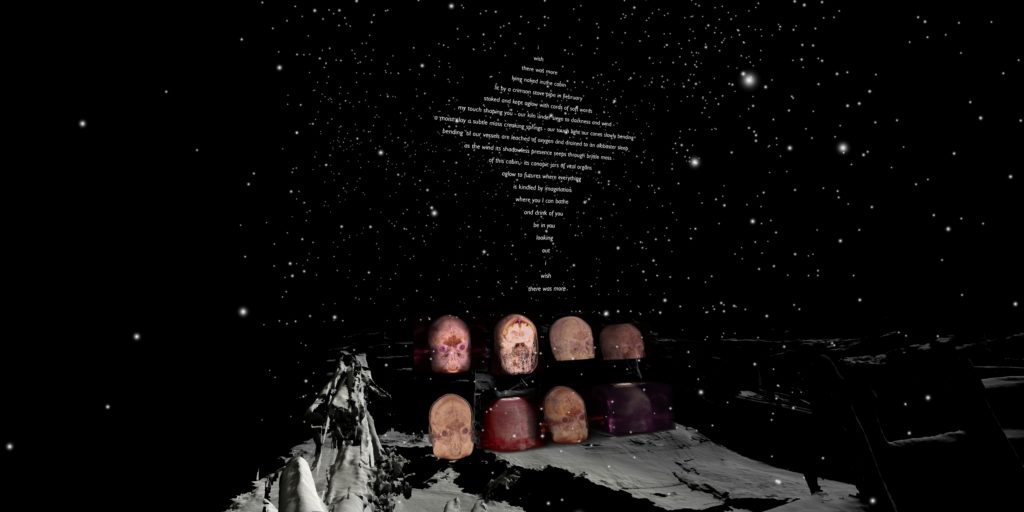

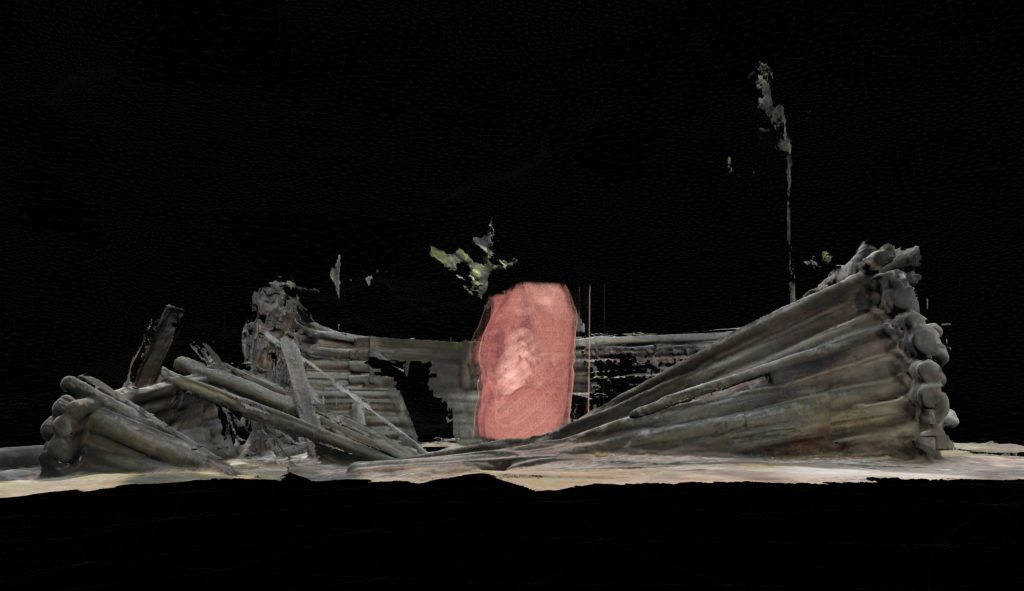

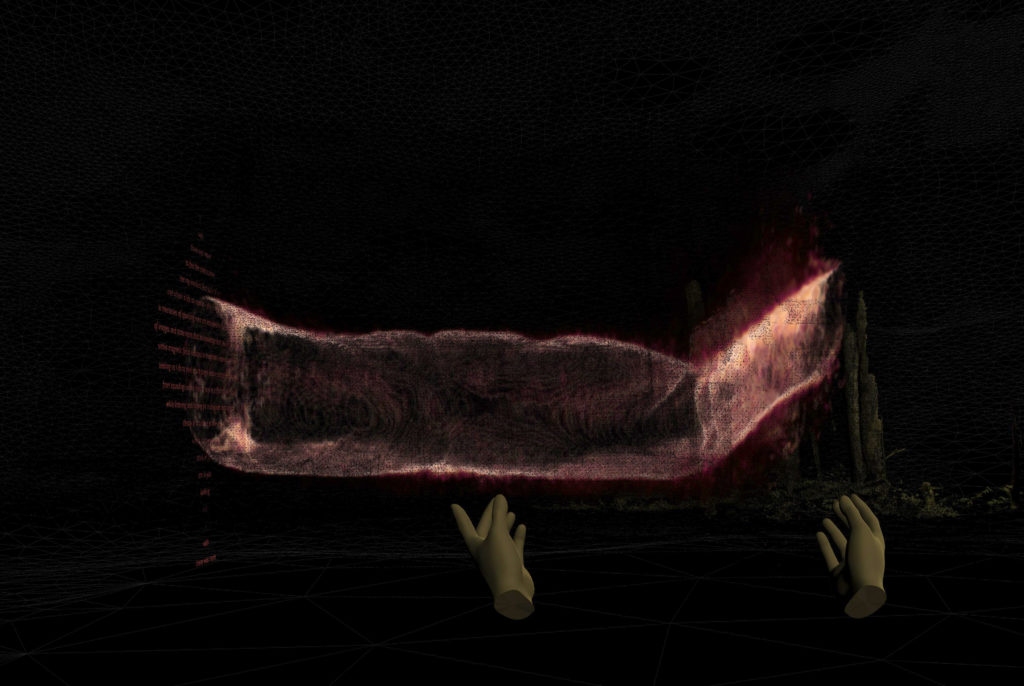

In order to counteract the ethical dilemma posed by this potential lack of consent, Oliver and her collaborators made an open call for scan data to be donated willingly for a creative project, with the informed and ongoing consent of donors. In the second scene, the donated data swirls in three concentric rings around the viewer. Data from Oliver’s close family and friends is in the first ring, the information provided by known colleagues is in the second ring, and the scan data from less familiar colleagues, or “friends of friends,” populates the outer ring. As users move closer to the scans, they hear human voices that either recite or sing the words of “Touch,” another poem written by J. R. Carpenter; the poem washes past them as the scans continue to swirl around the scene. Artist Liz Ingram was among those who generously responded to the call for scan data. She donated over twenty datasets, produced for diagnostic purposes since 2014 as part of her ongoing oncological care. Ingram had already created several artworks with her own medical scans, along with her husband and artistic partner Bernd Hildebrandt. After a series of conversations and experiments, Ingram and Hildebrandt joined the collaborative Your Data Body project, taking aesthetic control of the scenes that feature Ingram’s data. Ingram and Hildebrandt combined her medical scans with LiDAR scans of disintegrating wooden cabins near an Alberta boreal forest lake, a location that is central to their emotional lives past and present. They thus physically grounded the data, even as they enlivened the cabins, portraying them as richly haunted ruins that contain memories of bodies that once glowed with warmth. This experience is enriched by a soundscape constructed from the field recordings made onsite by Scott Smallwood. At the same time, each scene contains a poem written by Hildebrandt that either floats above Ingram’s data, is nestled within it, or, as in the final scene, sways back and forth through it. Hildebrandt wrote the poems after seeing renderings of his wife’s data and feeling a deep sense of lack in them ⸻ a lack of recognition, a lack of ownership, and a lack of meaning. The poems are tender, mournful, sensuous, and full of longing, recalling shared intimate memories of each other’s bodies in a specific location steeped in personal and socio-political history.

Marilène Oliver (she/her) is an associate professor of printmaking and media arts at the University of Alberta. A settler scholar, Marilène works at a crossroads between new digital technologies and traditional print and sculpture, with her finished objects bridging the virtual and the re(al worlds. Oliver uses various scanning technologies, such as MRI and CT to create artworks that invite us to materially contemplate our increasingly digitized selves. Marilène currently leads two art & science research projects at the University of Alberta: Dyscorpia: Future Intersections of the Body and Technology and Know Thyself as a Virtual Reality.

Scott Smallwood (he/him) is a sound artist, composer, and performer who creates works inspired by discovered textures and forms, through a practice of listening, field recording, and improvisation. In addition to composing works for ensembles and electronics, he designs experimental instruments and software, as well as sound installations and audio games, often for site-specific scenarios. Much of his recent work is often concerned with the soundscapes of climate change, and the dichotomy between ecstatic and luxuriating states of noise and the precious commodity of natural acoustical environments and quiet spaces. A settler scholar, he performs as one-half of the laptop/electronic duo Evidence (with Stephan Moore) and teaches as a professor of composition at the University of Alberta, where he also serves as the director of the Sound Studies Institute.

With a background in industrial design, graphic design, and sculpture, Bernd Hildebrandt (he/him) plans exhibit spaces, designs display furniture, and installs exhibitions that integrate objects, images and words. An interest in writing poetry sparked numerous collaborations with Liz Ingram. His poems are integrated into the fabric of her often large-scale images and prints. Working together has resulted in installations exhibited around the world since 2011.Liz Ingram (she/her) is currently Distinguished University Professor Emerita at the University of Alberta, Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, and Member of the Order of Canada. A settler scholar, she works in various media, including etching, lithography, digital print, and installation. The human body and the elemental in nature are recurring sources for her art practice, which investigates issues relating to the fragility of life and the environment. She has exhibited internationally and often collaborates with other artists, including Bernd Hildebrandt.

Scene 1

Artist – Marilene Oliver

Sound – Scott Smallwood, Catherine Bevan, Mari Alice Conrad, Thomas Powell & Madrigal Singers Choir, University of Alberta

Unity development – Walter Ostrander & Dhara Pancholi

Secondary use of anonymized scans from TCIA, National Library of Medicine, Embodi3D, National Library of Medicine & Open Neuro.

Scene 2

Artist – Marilene Oliver

Sound – Scott Smallwood, Catherine Bevan, Mari Alice Conrad, Thomas Powell & Madrigal Singers Choir, University of Alberta

Poetry – J.R. Carpenter

Unity development – Walter Ostrander

Secondary use of donated scans

Scenes 3-5

Artist – Marilene Oliver, Liz Ingram & Bernd Hildebrandt

Sound – Scott Smallwood, Catherine Bevan, Mari Alice Conrad, Thomas Powell & Madrigal Singers Choir, University of Alberta

Poetry – Bernd Hildebrandt

Unity development – Walter Ostrander

Secondary use of donated scans